As to teaching and teachers, I hope that quite a lot of ideas may already have been presented in my previous postings, but I’d like to add and elaborate further.

Most importantly, I think that interaction, speaking and revising are also the main areas which most teachers tend to forget about, unfortunately, though in the name of doing good to the customer.

Teacher (Photo credit: tim ellis)

Very often, in more traditional classes, especially with very low frequency lessons, there’s no time for listening practice at all. By that I don’t mean that students don’t have the opportunity to listen to their teachers – oh, yes, they do the talking all the time very often. The problem with that arises if they either talk in the students’ native languages, which happens all too often in China, but probably, as I’ve already mentioned, in the Netherlands, and even in other countries as well, or if they don’t really stop talking – to check the understanding of their students, that is. These two cases are definitely not cases of time well spent to a smaller or greater extent and can’t be counted towards listening practice. There’s no practice without a degree of interaction, and more precisely, not without performing a task in the meantime. That can be done even while the teacher talks himself/herself, but can’t be done with the teacher talking incessantly.

English: kdi students listening to professor in class (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Teacher talking time, or TTT is very important for students. Let’s not forget that if nothing else, the teacher is the basis for a while for the aural/oral perception of the foreign language, and even if there’s some systematic work on listening with taped native material, he or she is the most frequent example to follow. Without examples, spoken language can’t be formed, thus no interaction can be expected of the learner. On the other hand, extended solo lectures are also not enough basis for interaction, and can become utterly boring and counter-productive in the long run. While talking, the teacher should at least frequently stop to ask the opinion of the students, which provide incentive to talk and also feedback to the teacher about understanding. If this latter fails, TTT was useless, and the nature of teaching should be adjusted approriately.

Very often, in more traditional classes, especially with very low frequency lessons, there’s no time for listening practice at all. If there’s a listening part to an important test for the students in the country, teachers tend to run a few practice tests through without discussing the results and parts of the test, so the learners have no idea about the reasons for some answers that they have missed, they have no chance to pick up the odd piece of vocabulary, they only have the tension of concentrating on several tasks at the same time for an hour: reading and understanding the questions, listening to the material and then making logical decisions, which, however, often doesn’t happen on the basis of the material heard, only on the possible answers. In many cases, if someone is weak in the language, or is taught with translation, he/she also has to translate the questions for himself or herself. A very tall order to succeed. Even so, in many cases there’s no time for a re-run, as I’ve experienced it in my Dutch classes, and anyway, the real tests also demand that the applicant listens only once.

Instead of this, according to English teaching traditions, even the highest-level language exams (Cambridge First Certificate, Cambridge Proficiency, IELTS, TOEFL, PTE General, PETS) allow the student to listen to texts twice and adjust their answers with the second listening, or with BULATS, the computer adjusts the listening and the question to the applicant’s previous answer. This follows an understanding of the workings of the brain, which needs first wider contexts, and often also adjustments to what has been heard before it can make informed decisions on details. This is why, for testing purposes, we need a second listening opportunity.

But this is only a question of testing methodology. The other, more important question is whether the students receive proper listening practice before that all-important final test, or are left to practice on their own, or perhaps not given anything in this direction. It sounds obvious to me that listening skills need to be built up just like grammar skills, from easier to more difficult, originally with a strong focus on language already covered and cutting out the kind otherwise. But not for many of my colleagues. Moreover, learners need appropriate activities and tasks to perform while listening. From answering general questions, through following the text with the script to gap-filling, re-arranging the text and repeating some sentences or items of important or problematic vocabulary or grammar should feature strongly among the techniques. These should be varied quite often and all should be ‘do-able’ so as not to frustrate the students but build up a proper understanding of the text.

By ‘do-able’, we usually mean that for developmental purposes, we are not supposed to ask deduction questions right at the start, or the kind that need outside knowledge. We should also not ask questions on passages that are unintelligible, difficult to follow even for native speakers, or demand spelling of unintelligible, or items not yet learned. Asking the students to write a series of answers only after a whole listening passage is also above most learners even at higher levels for the sake of practice. Giving answers in full sentences in response to listening is not a do-able task even when the text is broken down, at least on lower levels.

Instead, we can first ask near-beginners, for example, how many people talk and in what situation, what’s the relationship among them, and the like. Fill-in questions in the later stages should not contain groups of words, rather parts of groups where the other part helps understanding by making quess-work possible. In any case, expected language is a lot more understandable than the unkown or unpredictable kind. The listening passage should not contain non-understandable, unpredictable grammatical items that haven’t been introduced. If we want to introduce grammatical features, we should use it with items that are not difficult to hear.

There’s also debate about how long a ‘do-able’ listening passage may be. I myself have experienced in my teaching as well as my own language learning a very sharp decline of general attention after two minutes, often, at lower levels, even after one minute. With a foreign language, long-term memory on the basis of the logic of the text doesn’t work nearly as well as with our own, or on high levels of language competence. Before the student can think in the target language, he relies only on short-term memory, which mostly relies on understanding each and every word, interprets them and puts them away shortly. After a while, while the listener is still struggling to understand and interpret the ever-flowing following items, earlier memories quickly fade and the task becomes impossible to execute. Rather, such a long task above the student’s level of competent understanding will execute the learner.

I may here add as an aside that this is to a large part the reason why simply living the everyday life of a foreign country trying to learn the language doesn’t work in itself for a few years for most people. Without getting help in interpreting the language showering the new-comer, he or she will be inundated so much that exhaustion takes over very soon for a long time. Some formal help is also needed. But it’s also true that work or some other special activity that demands absolute attention and provides the ultimate need for learning (as I’ve pointed out elsewhere) can also speed up the learning process very effectively if there are helpful people around. Workplaces may not be ideal, but partnerships very much so. At later stages of development, all immersion kind of situations do so too.

Dictation seems to be a good listening task, but while it is also a writing task, we mustn’t forget that it relies on no understanding of the text much and it’s not creative at all. Above a certain level, when students have little problem with the spelling of individual words, normal slow dictation tends to become very boring and even counter-productive. As a result, some students may commit mistakes they wouldn’t in creative writing because of over-confidence, or get no benefits that they could carry over to their creative writing, when they only focus on meaning, still committing mistakes they no longer make in dictation. At levels starting at mid-level, scripting of videos by native speakers without the intention of dictating could be set as task, but with several rewinds if necessary. The difference for the learners’ hearing abilities between live dictation and machine sound from videos can still be huge, so this is the phase to be practiced carefully because at exams, machine sound must be decoded while performing additional tasks.

Such advice can be extended for quite a while longer, but I’m sure it’s already understandable enough. These types of points can also be extended to reading tasks as well. Part of the reason is that just as listening is a necessary basis for talking in oral interactions, reading can be understood to do the same in written interaction. Similar questions can first be put to students about the general meaning of the text, by way of fast extensive reading. Once the context is worked out with this help, more specific questions can be asked and activities can lead to intensive reading within the borders of boredom. Here we can come back to the general demand for teaching in interesting ways. On the one hand, both listening and reading material should be introduced by discussions or at least a few well-designed question about the possible meaning of the text and the feelings of the students about the topic. On the other, we should provide enough room after listening and reading tasks for discussion before the whole activity becomes boring, by which I mean overworked. Before discussions, more detailed work can be done on specific language items like grammar, or vocabulary, of which reading is the most fool-proof means of development. But if we don’t ask the group for their opinion, we have only done half of the useful work, because we haven’t activated the material just heard or read. Active use in post-listening and post-reading activities revise the meanings, vocabulary and grammatical features of the text in a way that involves the learners deep, if interesting enough for hem, making the activity memorable.

Which means that it’s more important to devise and carry out discussions than reading. We can set up interactive tasks just as easily as reading tasks, but interaction can happen preceding, following or instead of reading, the most important point being that it can’t be neglected for fast learning of the target language. Culturally, Far-Eastern, or South-Asian, Middle-Eastern cultures may pose a major obstacle to interaction if they demand absolute quiet and attention concentrated on the teacher most of the time. People of those cultures would find little help towards their interactive oral skills. So, as far as behaviour is concerned, the relaxed atmosphere of relatively free Western cultures can provide a lot more possibility for language development than stricter cultures. Sometimes, though, the infamous misbehaviour known from Hollywood films is also a major obstacle of course. I can assure everyone that the same may face you in Hungary or China if you try the appropriate places, and the one principal in the Netherlands I’ve talked to also warned me of behaviour special only to Holland, although, I suspect, she has had no experience of the same in said countries where I have. But that’s another story, perhaps pertaining to the headline ‘pigheadedness in education in the Netherlands’, where I have to stop before I can also be accused of the same.

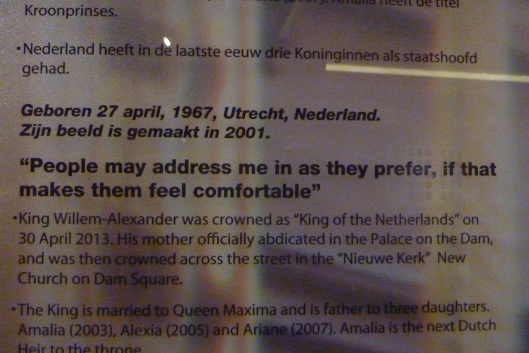

‘balloon debate’ in Kitto college, near Plymouth

Extreme cases of misbehaviour aside, speaking and interactive tasks must often be given after careful planning. For whole activities, asking just a couple of simple interest-raising questions may not be enough. There must be a task to be performed with and end-result to be achieved. Task-based learning and role-plays are effective because, paradoxically, they steer attention away from the language necessary for them to be performed. Students are less controlled in such cases and, consequently, feel less inhibition to express their preferences and opinions, all in pursuit of a common goal of the group. Role-play also allows them to change personalities, which is often very exciting, but not for everyone and not at every age, so discretion should be used when assigning such tasks. In more elaborate and complex cases, the activity works like a simulation, without computers, naturally, but with real roles for everyone involved, which may help the more reticent ones.

It is sadly usual that, if such interactive tasks are given at all, feedback is not asked in return at the end. Except in very strange cases of group dynamics, the whole class would find it interesting to get a glimpse of what other groups thought about the case in question. Feedback serves as a satisfactory closing down of the activity or a whole study period and also serves to revise and reinforce some items of language that may be important for all. Good interactive tasks usually also serve as natural basis for written work, as homework in cultures which use it, or at following classes in cultures where homework is not often used, for example in the States or Britain.

Furthermore, there are strong arguments to using discussions not only as planned. With the multitude of different kinds of learners in each class, every single lesson planned the same way for different groups naturally tends to, and should be encouraged to, go in different directions. Differences should be encouraged and will surely emerge if the students are allowed room to contribute to the proceedings. They have a right to do so, they are the customers, we have to provide for all of them. Besides, providing for them doesn’t necessarily mean we have to give all the answers: we are there to provide the framework for learning, and that framework includes all members of the group with their differences. Consequently, they should be invited to discuss and give answers if necessary to problems other members have. On questions of grammar and vocabulary usage, it’s mostly the teacher who is best positioned to decide on best answers. In other cases involving opinions and decisions on tasks, better leave the group to decide for themselves, like with the ‘balloon debate’ represented above with my photo.

English: Some of us and our teacher, having fun while understanding curcuits (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

What a teacher must under all circumstances care for is that debates and discussions do not lose their aim and become loose and limitless. A friendly teacher would do well starting a lesson with personal questions of interest to the students, but that should lead towards a point and not become an hour of talking about how they like the latest music. Chatting on the level of teenage street conversations is also important but its level is not enough for foreign language development after a short while. After that, nobody can take home anything new. So it is up to the discretion of the teacher and his/her flexibility do decide when to channel introductory chats into learning.

I’m sure that I don’t need to discuss handling grammar here. Most of my readers, I think, are professionals and grammar is the area almost everybody feels comfortable with enough. The only remark I’d like to make is that, as I earlier warned, grammar should not be overdone, especially with the mostly isolating languages, those without differences of forms of words. On the other hand, word forms of agglutinating and fusional languages, those with a lot of changeable affixes and forms need to be thoroughly drilled before higher levels of understandability and fluency can be achieved.

I do, however, feel the need to talk about the good old ‘grammar-translation’ method. Quite a few teachers in Middle-Europe, those who have connections through teachers’ associations, the BC, meetings, conferences and summer courses, those who manage to and willing to keep up with English-teaching methodology in Britain and the USA have long ago refuted this method. Yet, I meet colleagues and students from time to time who try to stick to it. I’ve meet them not only in China, where, as I’ve described the situation in an earlier post, it is still widely in use, for lack of anything better known to many, but here in the Netherlands and also in Hungary.

For people so inclined, I’d like to point once again to the intricate ways the brain has to take to process information both ways when trying to translate, which is not only difficult but also extends reaction times, especially because it almost always involves writing down the translation, and writing is already a lot slower than speaking. We can say, then, that this method reduces the possibility for using a lot of language within any given period, while it demands levels of knowledge that the learners are still only striving for. For translating a text, we must be in full command of both languages, which is not the case all too often. No wonder that translating and interpreting are two very demanding high-level professions very distinct from teaching, and are taught those already in full command of the target language. I can hardly imagine a slower and more dragging method than this for lower-level learners. Translation is also conspicuously missing from internationally accepted English language tests. Teachers using this method should at least keep this in mind. But one thing is sure: the conservatively or intellectually inclined students can feel after such a lesson that they’ve been given something, they’ve achieved something during the lesson: they’ve understood a text now. Alas, this hardly helps them communicate better in the target language if it stays the only method of teaching/learning.

With this we’re already at vocabulary practice. While the system of grammar structures can, with good, ordinary practice, listening, reading or writing, also be acquired, particular words and word groups may resist memorizing until the language system is internalized. Until then, a lot of rote learning may sometimes help, but even afterwards, words must be practiced and recycled systematically. The house won’t stand without its building blocks.

The original source of vocabulary is necessarily the teacher. For good results, we do our best starting our very first lesson already in the target language. In this way, they find it natural to try and think in the other language already at the outset and find it gradually easier on the way, getting used to it quickly. Not much time is lost on thinking in two languages, trying to translate everything first, then translate it all back to the target language. At the same time, care must be given to meaningful vocabulary work all the time, avoiding unnecessary and rare items until much later or perhaps never. The aim is not to teach them everything, but to let them develop their second or foreign language competence as fast as possible and prepare them to respond in and to likely situations and language use. Unlikely, old-fashioned, too formal phrases don’t have much place in EFL classes. They can learn them later if they decide to specialize in the literature or linguistics of that language.

I could even say that vocabulary is one of the greatest responsibilities of the teacher, because the learner is inclined to forget the new words even in their own language and can at home tell his/her father that they haven’t learned anything today. The student must be made to keep a vocabulary booklet of his/her own from the start, it should not only be encouraged but regularly checked. But not only that. Because of the forgetfulness of the students, the teacher is responsible to make sure that the students also remember the words covered. The teacher must explain the new vocabulary and important idioms, and soon must recycle it – within the same lesson, at the next lesson, or even next week. I understand how difficult it is for us to remember with each group what items we’ve taught, but we can keep track of it ourselves too. It’s a nasty argument if later students start grumbling that they were tested about vocab they’ve never properly covered. If that happens, as it quite often does, I sympathize with the student. Of course, the student is responsible for his/her own work on the language, but without help, he or she is at a loss and can’t cope.

After good introduction of basics of the language by the teacher, to make sense of vocabulary regularly and to revise it, learners need good dictionaries in the first place. Only good two-way dictionaries can help, those that not only give one supposed meaning to the target word in either language, like some weaker Dutch-English dictionaries do, though the ultimate horror sometimes comes from my Chinese-English double dictionary published by Oxford UP, which, if I randomly open the Chinese part, may come up with a Chinese word like 衰 (shuāi) and give me ‘decline’ as translation. Does it then mean ‘get smaller’, or ‘refuse’ like in refuse an offer – or a request? There are example phrases that help with this one, but far from everywhere. Also, smaller and simpler dictionaries either don’t give example sentences, or give no idiomatic phrases at all in which the words are used. Soon, learners will find such dictionaries inadequate. On the other hand, at later stages, single-language dictionaries can become more and more useful as they become increasingly usable, when the learner has reached a level on which he or she can think in the target language. So, if possible, we have to give good advice on which dictionaries students should buy for their money.

Even if the learner achieves the ultimate aim and can think in the target language fluently, the teacher has his/her role to the end. Because it is so difficult to reach that ultimate aim, the teacher should focus on working towards that aim providing guidance and structure to learning in class and for home work as well and caring for recycling all the way. He or she should also see to it that the language is learned in a complex way, not only as individual skills. I find a so-called ‘grammar lesson’, or ‘vocab lesson’, or ‘listening practice lesson’ as full lessons very strange. All the skills had better be mingled, providing new angles to ideas and new ways and expressions to utter them.

Student teacher in China teaching children English. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Now I’d like to add something about what is not really necessary to do in school classes. One such thing is too much translation. Words or idioms may be translated if necessary, but real translation is a completely different skill to the usual four skills. It had better be avoided, especially if the language levels of students is relatively low. How could they then benefit from translation, a complex skill requiring total competence in their own language as well as the target language, if they don’t have a complex competence in the new language? No wonder that most Chinese students, who also suffer from inappropriate language patterns to follow, fail miserably after a decade of being taught English 6-8 classes a week, while their abilities at repetition is outstanding, as attested to by the fact that they manage to learn the tens of thousands of characters of their own mother tongue. No mean feat. The reasons can be found if we think about how important creative, interactive use of the language is, how inefficient sheer word-repetition is, and how futile it is to translate from or into a language that you don’t understand or can’t use in the first place. Studying their own characters happens in the context of their mother tongue, it’s not something out of thin air, as words of an unused language are.

Another thing that has little place in purposeful class work is using complex tests. The Chinese prove its futility too. But above that, we have to remember that most tests are used as the measurements of achievement, so they should be treated as such, not more. Fortunately, there are tests devised for assessment of development. In this case, however, the students must be well prepared for them, meaning that they should contain material already covered in a re-structured way. They serve the teacher to be able to ascertain how far his/her students have progressed. Using the large, general test instead of this kind only frustrates students.

My usual approach is that once the language is properly acquired through purposeful and well-constructed activities, practice tests among them for structures and vocabulary too, the important, hot assessment tests, for language proficiency tests or university entrance test, for example, will be taken care of by the skills acquired along the way. Sitting through examples of these kinds of tests are necessary as far as the need to experience the feeling and the structure is concerned, but repeatedly doing them is overly and unnecessarily tiring and purposeless, because most of the time they’re so long that they can’t be properly discussed, though that could lend some usefulness to them. That discounted, better keep with meaningful interaction in class. Correcting usual written work, compositions, grammar tasks is enough to keep the teacher up some of the night alright.

Now a late addition to this post. It seems obvious that although language teachers usually speak in terms of the four skills, development of the students’ language use often happens, or rather should happen, along different lines, and particularly without using tests in the first place. I’d like to point out, too, that the role of the fifth skill, translation, should be reduced as much as possible. Instead, active use of and thinking in the target language should be promoted, especially using the sixth skill, that is, thinking! For anyone having doubts about its applicability or being in need of related methods, I’m directly providing a link here to a very interesting article which leads on to the details of the methods themselves: It’s about The Learning, Not The Tools.

Some final words. We can use a wide scope of methods that we think is best suited to our students, but we are only human, and not omnipresent or omnipotent. Consequently, there may always be a few students who we can’t help. They are also human and may have their priorities far from our classes. Don’t let yourself be disheartened by failures, you also learn from them. On the other hand, real results tend to come slowly. We may only see them many years after our work is done.

by P.S.