Tags

Amsterdam, English as a foreign or second language, English language, Madame Tussauds, mistranslations, Translation

Various places on the web and elsewhere expose the terrible mauling of the English language in China, one of the latest editions coming on the Chinese language blog here. Although this last one is called ‘tasty Chinglish’ on account of the fact that the examples come from food names in restaurants, this whole development of the ‘fan-club’ is beginning to become rather tasteless to me. After a visit to Madame Tussauds in Amsterdam, I thought, why not start looking at other ‘…lishes’?

‘Dunglish’ seems to be quite over the top, but let’s consider the distances, geographically, historically and linguistically, between English and those two countries. China used to be one of the doormats on the way to riches the imperialist mighty cleaned their feet on a hundred years ago. China got into such a terrible state of affairs as a result partly of this that they chose to follow the Chairman, who, alongside guiding the country out of the deepest doldrums and almost led it into just another one, kept grounding salt into the already bleeding wounds. He also cut the Chinese away from any foreign influence, umpteenth time in the country’s history. This also meant that practically no English-speaking people got into contact with any ordinary Chinese between 1949 and 1976.

This was easily a full generation, if not more, who were not only unable to learn languages but who also grew up loathing any foreigner. Coupled with long and repeated historical maltreatment before, no wonder a ‘foreigner’ is still mostly called a ‘laowei’ (老为), meaning ‘foreign devil’ by Chinese people in the street. Add the distance of kind between this Asian type of language and Germanic English, and the thousands of miles to English-speaking countries, hardly balanced by a few thousand native English people, or highly qualified non-native teachers teaching English as a first foreign language to an ocean of 1.3 billion natives, and you’ll see the enormity of the task. The enthusiasm leading up to the Beijing Olympics helped several thousands to master English, but the ratio is still tiny. And to critics from the West, may I ask which of you learned writing the Chinese sign system besides the Latin ABC? They do both en masse.

Considering that Dutch is a young Germanic language, in close proximity of kind to English and to the Islands themselves geographically, what extent of mistakes, if any, would be allowed for Dutch texts? Obviously, there aren’t enough English speakers to translate or correct all public signs and restaurant menus in Beijing, let alone around China. On the other hand, the Dutch are one of the nations that stand out in foreign language skills in Europe. Whereas there is one English-speaking television channel in China, whose text is locally made, English-speaking channels are easily available for and popular among youth in the Netherlands. The historical opposition between the two countries hundreds of years ago long forgotten, the linguistic kinship also adds to the expectation that here in the Netherlands all public texts in English are excellent. The testing methods in schools that I exposed earlier in this blog somewhat dampens this, still, what I’ve recently found in one of the most widely visited museums in Amsterdam, in Madame Tussauds, is nearing the level of shamefulness.

As I see it, it can hardly be argued that the third sentence explaining Stuyvesant’s importance is a quote from the man himself. He probably didn’t speak English, the ultimate foe for his country then. This is the work of a Dutch translator who translated this text from the original Dutch for the sake of English visitors. Still, he failed to change the sentence structure from Dutch into English.

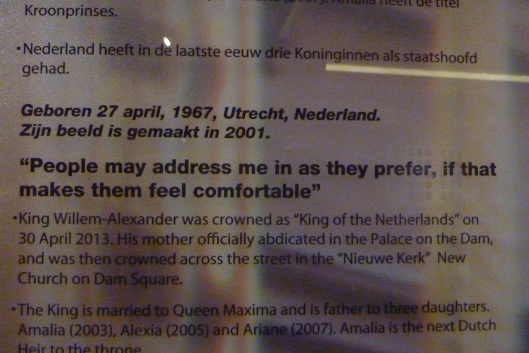

This was perhaps the greatest blunder I found, but there are number of other, smaller ones that should be improved by the museum. This one, for example, is a close contender.

Not only do we not address him ‘in’ as we prefer, he was also not crowned ‘as’ king (see the example here, he was still a prince when he was crowned king of the Netherlands, although “Today, only the British Monarchy continues this tradition as the sole remaining anointed and crowned monarch,

though many monarchies retain a crown as a national symbol in heraldry” according to this source. However, it is simply hilarious to believe that his ‘mother officially abdicated … and was then crowned’. This would mean that his mother is still the sovereign following an anointment for the second time after her abdication. The writer simply forgot to include ‘he’ to signal a change of the subject.

In the following example of manhandling English, ‘june’ spelt with a small letter, like ‘april’ in the one above, is a minor issue following the Dutch vernacular.

Unfortunately, “The” following a “:” should not be capitalized, but the ‘sentence’ afterwards is meaningless simply because the “Artist, also known as TAFKAP and, was christened Prince Rogers Nelson after his father’s jazz band” is not a sentence. It’s not the senseless inclusion of a comma before ‘was’, but the inclusion of “and” that makes it so, making the following into a clause that would need another subject, or an object, before going on with the predicate. Then, “Besides the more than thirty albums he released, Prince is the charismatic owner …” is also not exactly the paragon of the correct subject co-ordination, making Prince another version of, or name for, the thirty albums he released. A little bit massed up, for my taste.

Then let’s consider another nice one, which also misses the capital on “may 5”.

A couple of blunders here. The smallest of them is that it’s a normal text, so “Debut album” badly needs an article in front of it, on account of ‘album’ being a countable singular noun. Further, in a text in the past tense, we suddenly encounter “leads” and “breaks”. Yes, historic present, but then what about the rest of the text? All of it should either be in this historic present, or the writer should have kept the past, where he returns in the third part after all. But funniest of all the mistakes here is in the first and second line – “and that friend out her song …”. Fried out, friended out, ousted? That friend outed? What’s going on here? Would ‘published’ or ‘brought out’ have been so difficult? “amoungst” in the last part is only the icing on the cake here.

Perhaps we could only find the usual non-capitalized name of a month and the inconsistent use of the comma in the following …

but this also allows one to see that the writer can’t differentiate between defining- and non-defining clauses, making it seem as if there had been at least two “Idols 2” competitions. Besides, “recordcompany” is a non-existent word, the idea must have been either a recording company, or a record label, or perhaps a record-company like here. I also suspect that they actually have a recording deal, not a record deal, which would perhaps mean a record amount of money for the deal; however, this seems far exaggerated, without real international fame for the said duo. I can simply accept the missing question mark after “Do you know what I mean’ … it may have been missing from the original as well.

The usual ‘july’ and ‘october’ aside, I have a certain measure of doubt as to whether Rembrandt could have painted anything not “in his life”, but I’m certain that even he could not paint etchings and drawings, not even with his outstanding talent, and not in the hundreds and thousands. Further, if the writer knew that the Saxon genitive could be used in the case of “Amsterdam’s “Rijksmuseum””, how could he have not known it with “Rembrandts work”? Or did he get enlightened between the two sentences? The missing commas in the last sentence are a completely minor issue after this.

In this last example of Dunglish, the second question is a fine piece. Not only because, in English, the what he received comes before the where from, but also because, sadly, oevreprice is not English. Oeuvre is the legitimate word in English for the work of an artist over his lifetime, but a prize for this work is called a ‘life achievement award‘, or ‘lifetime achievement award‘. It’s a small matter that, by the third question, the writer forgot that he had started to list questions after the original “Did you know that …” piece, otherwise he wouldn’t have started the third dependent question with a capitalized “He”. But he certainly never forgot to write all names of months without the English capital, so why so forgetful otherwise?

Well, I know a writer/translator can’t be perfect. That’s why translations are proof-read afterwards, before the texts are handed out, as done and dusted, to be presented to the original client. Obviously, at this very exposed museum, somebody forgot to care about this, and nobody else cared to notice. I hope that somebody does after this. But I have become a bit uncertain as to the seriousness of mistakes on English-language signs and texts in China. In which country of these two are mistakes relatively more serious? Besides the need for Mme Tussauds Amsterdam to check and exchange their notices, perhaps the image of the Dutch being excellent about their English also needs a revision. And berating the Chinese for their public English texts could also be done a bit more kindly. To ease the stern expression on Mme’s face.

Well, I know a writer/translator can’t be perfect. That’s why translations are proof-read afterwards, before the texts are handed out, as done and dusted, to be presented to the original client. Obviously, at this very exposed museum, somebody forgot to care about this, and nobody else cared to notice. I hope that somebody does after this. But I have become a bit uncertain as to the seriousness of mistakes on English-language signs and texts in China. In which country of these two are mistakes relatively more serious? Besides the need for Mme Tussauds Amsterdam to check and exchange their notices, perhaps the image of the Dutch being excellent about their English also needs a revision. And berating the Chinese for their public English texts could also be done a bit more kindly. To ease the stern expression on Mme’s face.

by P. S.